MEIERLINK

Vampire Gothic Lolita ADN Mutated

- Gender

- Male

- Guildcard

- 42031692

PSO RETROSPECTIVE

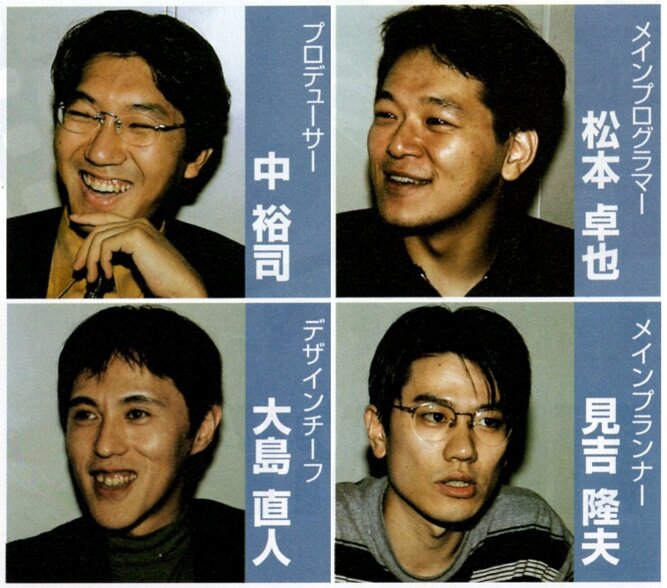

Interviews with key members of Sonic Team from Phantasy Star Online's development on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of PSO.

Interviews with key members of Sonic Team from Phantasy Star Online's development on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of PSO.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

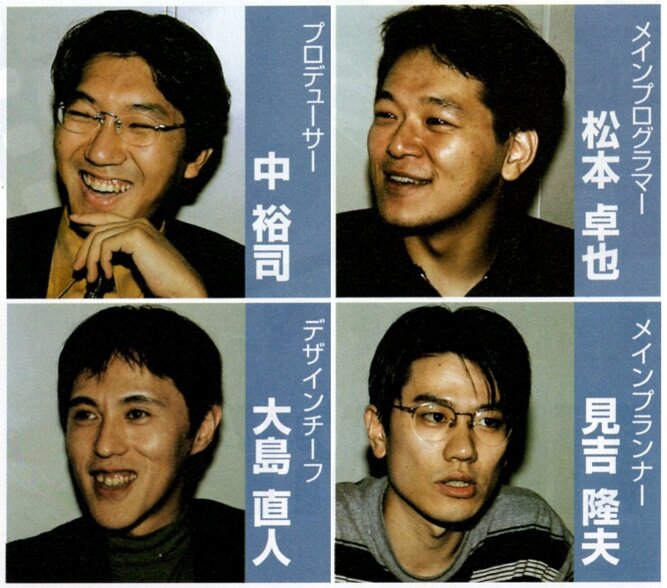

Part 2 : Takao Miyoshi, Phantasy Star Online’s director talks Diablo influences, cut features, and Christmas Nights.

The web page from which the original interview is taken can be found here

Let’s start by having you explain your role on the team. You were the director of PSO, but that can mean a lot of different things depending on the situation.

Let’s start by having you explain your role on the team. You were the director of PSO, but that can mean a lot of different things depending on the situation.

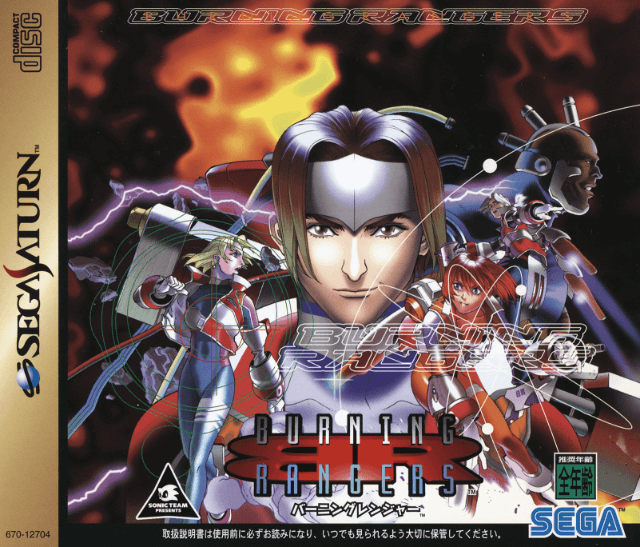

Takao Miyoshi: I did the planning and original concept for the game. [...] I was more of a director and supervised the overall project. At first the planning document was just a single piece of paper, then it expanded from there. If we go back to the very beginning of it all, it goes back to the Sega Saturn. We were trying to make an online game on the Saturn for a long time. That’s when we first started exploring online gaming. At the time, I was working on a game called Burning Rangers. It was initially created as a network-compatible game with four players who go on a rescue mission. But there were network issues that we couldn’t overcome, so it was released as a regular, offline game. That was a game that I had created with online in mind but [in which the online part] didn’t make it past the planning stage.

Wow, Burning Rangers was originally planned as a four-player online game?

There’s a lot of flying around in that game and the maps are very complicated. So for PSO we said, “No flying allowed!” because that made things too complicated. That’s why you can’t leave the ground in PSO.

This changed for PSO2, obviously.

This changed for PSO2, obviously.

Yeah, you can jump and fly in PSO2. [But for PSO] we found that it became difficult to navigate your character when they were flying in a 3D space, so we decided it was best to keep the player on the ground.

It’s interesting that you mention jumping because when I spoke with the programming team, we discussed whether jumping was removed to avoid having to transmit too much data back and forth. It seemed like it was for practical reasons but now you’re saying that it was also for spatial reasons.

Yes, [program director Akio] Setsumasa handled all the server-related programming. He’s the one who said definitely no jumping in PSO. I concurred and that’s how we made the game. We had to decide what kind of navigation would be network-friendly. You might notice in PSO, it’s a lot like Diablo, where there are a lot of points that you can warp to. The reason why those points are so deliberately set is because if you’re playing online, there would be enough time between points where data could sync up and everyone playing would be in the same location. There wouldn’t be any lag where one player gets ahead of another player.

We’re approaching two decades since the game’s release, and you were 20 years younger when it came out. Looking back, what is your impression of PSO now?

I was about 30 years old when I created PSO and I quit Sega when I turned 40. I worked on the series — PSO, Phantasy Star Universe, and Phantasy Star Online 2 — almost up until the release of PSO2. So PSO was my life for about a decade. And now it’s been about another decade since leaving the series. Since that time, I’ve been studying and working on different things.

The thing that stands out is that I was so young. If I had known the complexities of creating and running an online game such as PSO, I probably would never have made it the way it turned out. I would have made prudent decisions and figured out how to simplify it. We didn’t really understand what it was going to take, so we took many risks and pushed things through. Consequently, that was probably the right move. The “Word Select System” is a good example. I don’t ever want to make something like that again.

Perhaps the word “recklessness” isn’t the right word, but that sort of risk-taking, where you’re less cautious because you’re young, is probably what allowed you to achieve a lot of what you did.

I’ve become wiser, right. I know that if I do this then that will happen. Which means I’m looking for efficiency and the path of least resistance. I think that leads to making familiar games where the path is clear and the return can be maximized. But at the time, everything was new and we couldn’t foresee anything, so every step we took was uncharted territory. There’s a certain amount of risk in that kind of environment and as you get older, you become risk-averse. When you’re young, you’re not thinking with your head, so you can charge into areas without even recognizing it as a risk. I think there was an element of youthful enthusiasm that pushed the game through.

One person that was not young at the time and supported the team was Isao Okawa, former chairman of CSK and Sega. He even pumped $800 million of his own money into the company at one point to make sure the development teams could continue to make games that only Sega could make. So here was an older executive at the top of the company taking risks, too.

PSO wouldn’t have existed without him. At the time, the No. 1 thing for Sega was how to blow people away by making something new. That was probably the biggest factor.

Yeah, it was a great period. PSO was a pioneering game and this was your first game as a director. How did you navigate through that pressure?

The pressure was intense. This probably won’t make it into the article but this was around the time when North Korea launched a missile over Japan and it landed in the Pacific. I remember thinking that if the missile had landed in Tokyo, it would delay the launch. It would cause such a commotion that we would have to delay the launch, and we would have more time to work on the game. [laughs] That’s how psychotic I was at the time.

Did PSO launch pretty much on time or did it suffer a lot of setbacks?

It didn’t launch as originally planned, but ... it came out in 2000, right? We wanted to release it before the 21st century, so 2001, and I think it came out at the very end of 2000. So, we just made the drop-dead deadline. But it was a forced release. There were still quite a few bugs left in the game.

Obviously, you had gained the confidence of Naka by that time. Why do you think he entrusted you to be the director of PSO?

Obviously, you had gained the confidence of Naka by that time. Why do you think he entrusted you to be the director of PSO?

Put bluntly, while I was the main planner for Burning Rangers, I also did the scheduling and solidifying of the game’s concept design, so I was practically doing the work of a managing director under the title of “main planner.” So, when it came time for PSO, I think they decided to give me the title. [Satoshi] Sakai was in charge of the art design, [Akio] Setsumasa and [Yasuhiro] Takahashi were in charge of the programming, and I was put in charge of the overall project, including planning. Naka was the producer, and basically came up with the overall vision of creating a global sci-fi RPG and handled the business-to-business situations, while I was the one who did all the promotional outreach and behind-the-scenes directorial types of things.

What sort of guidance and input did Naka provide during the development of the game?

Naka was very involved and provided a lot of ideas that were challenging to implement. He would tell me, “We should do this,” or, “We should do that.” Some of his ideas were seemingly impossible, but we would struggle and make them happen, and that’s how PSO became the final game. So I think that it’s thanks to Naka’s impossible orders that we were able to create something unique.

Because Naka began his career as a programmer, do you think that background helped him in coming up with ideas for the game from a producer’s standpoint?

Naka’s concern was not for how hard the work was going to be for the team. His concern was that the ideas were awesome and had to be included in the game so that the game would be great. His philosophy was “you don’t know until you try it,” and ideas didn’t stem from whether it was possible or “hey, this would help make our job easier.” They came from pure enthusiasm: “We’re going to do this, so you’ve gotta go make this happen.” So we’d take those ideas or problems, put our heads together, and figure out solutions. We were creating things that didn’t exist, so we would come up with possible solutions and try to convince him that what we came up with was practical and worked better than his initial ideas.

The process doesn’t sound super fun.

It wasn’t really fun, but it’s the way a genius works. He would never bend on his ideas. Once he had an idea, it was impossible to steer him away.

He was unwavering?

Some people would say that. He was very strict. But, that’s why we were able to accomplish something that wasn’t possible under normal circumstances. I think consequently that’s what made the game fun.

How did Sakai’s prior experience and talent affect the outcome of the game?

How did Sakai’s prior experience and talent affect the outcome of the game?

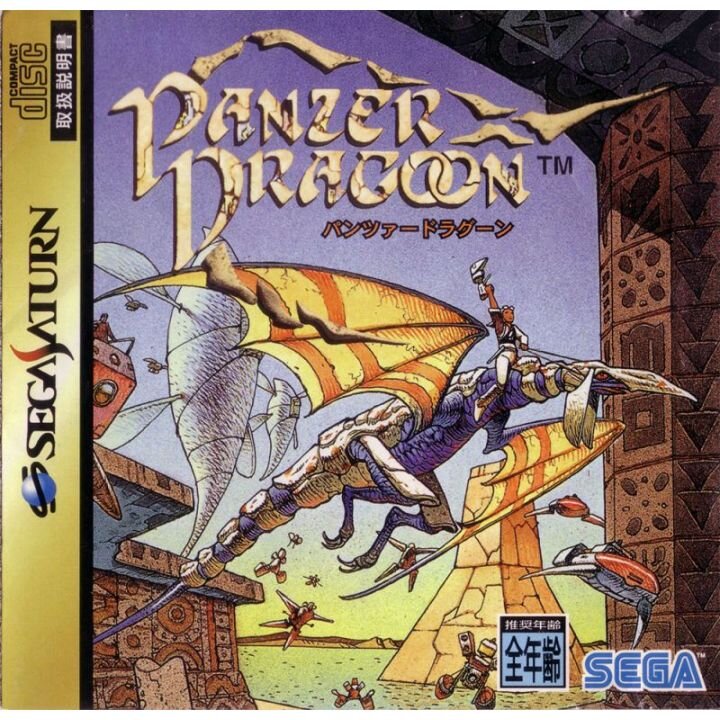

He was the [visual] designer for the game and established the game’s environment. You’ve interviewed him in the past, so I’m sure you’re aware, but he was the designer of Azel and many of the dragons in Panzer Dragoon Saga. I think PSO benefited from his prior experience, just like with all of us. My prior experience on Burning Rangers and Sonic games, Panzer Dragoon for him, and Setsumasa brought his knowledge of network gaming. It was a combined effort of everyone’s unique experiences.

Was Sakai responsible for the character designs and other areas?

He was in charge of the game’s overall visual design, including character design and style. His specialty is designing monsters and dragons. The dragon in the first big battle of PSO is quite symbolic. That was all Sakai’s work.

For Panzer Dragoon, he not only did the design for the dragons but also for the dragon ‘morphing’ system. He is an animator and a modeler who could do many things. Was he able to have a similar kind of impact on PSO? Players can change the size and shape of their created characters, for instance — was that idea part of his contribution?

For Panzer Dragoon, he not only did the design for the dragons but also for the dragon ‘morphing’ system. He is an animator and a modeler who could do many things. Was he able to have a similar kind of impact on PSO? Players can change the size and shape of their created characters, for instance — was that idea part of his contribution?

Yes, we utilized his experience from his work on Panzer Dragoon Saga with morphing the dragon, and decided to incorporate that into PSO, primarily because Sakai had the knowhow to do that.

Obviously, Diablo was a big influence on PSO. How much of Diablo did you play yourself?

I played quite a lot. Nobody on our team had worked on an online game, so one of the challenges was getting the team to understand what made online games fun. I had a lot of people play the game, but a lot of them were turned off by the dark fantasy. They would say, “it’s disturbing,” or, “I don’t get why it’s fun.” Trying to unify the team and getting them to understand the direction we wanted to take the game in was very difficult.

Did you have LAN parties, where you played in a controlled environment so that the team could understand the cooperative elements?

Did you have LAN parties, where you played in a controlled environment so that the team could understand the cooperative elements?

We installed Diablo on everyone’s PC in the office and had a closed LAN and spent many days playing together so that the team could learn what network gaming was all about.

Was there a point where you saw people starting to get the appeal, like the satisfaction of seeing a rare item drop, where you felt the team really get into the game?

Some people like Setsumasa stayed around until 10 or 11 p.m. at night after people left the office. He would connect Diablo to the network and play until morning, wake up to work, and then play again. Some of us weren’t going home much at the time. Some people would go home just to bathe, sleep a few hours, come back into the office to work, and then play Diablo at the office. It was mostly in the name of research, though. There are a number of games that we used as inspiration. Diablo was obviously one of them. I had heard that Dragon Quest was inspired by remaking Ultima with a Japanese audience in mind. So our concept was, “Let’s make a Diablo game that would appeal to the Japanese audience.”

With good results. Even though Diablo is a distinctly American game, PSO feels like a very distinctly Japanese game. And yet, it’s not just palatable to Japanese gamers but to everyone.

I think Diablo is an amazing game, but it’s not a game that appeals to Japanese players. Our suspicion was that Japanese gamers would prefer to cooperate and work together to defeat something more than to compete and fight against other players. That’s why we created PSO to be a cooperative role-playing game. Diablo has cooperative elements but it also has PK and an element of killing other player characters. We eliminated those elements and focused on how we could make a fun, cooperative RPG experience. I think that’s the biggest difference between PSO and Diablo.

The single-player in PSO is almost exactly the same as the multiplayer, though when you’re playing alone, it can be tedious because you have to zone out and return to attack before you get surrounded by enemies. When you’re playing multiplayer, that’s when something magical happens, because the cooperative elements make it so much more fair and fun.

We did adjust the difficulty level between characters for single-player and multiplayer, so single-player mode should have been a little easier to play, I think. The number of monsters that appeared was a little smaller, etc. It was our first online game, so we had to make sure that it could be played as a single-player game. But at the same time, we did spend a lot of time developing for the multiplayer experience, so single-player might have come off feeling a little more challenging.

Speaking of the online multiplayer experience, when the Xbox version came out, it was the first version where it was mandatory to be online. This was at a time when being online all the time was still difficult, due to internet speeds, lack of broadband, etc. You had to have Xbox Live even to play the single-player mode. A lot of people didn’t like that because you couldn’t play the single-player mode offline.

I forgot about that. I think it was Microsoft’s request. It was at a time when they wanted to make Xbox Live attractive, so I think they wanted a title that required Xbox Live. Of course, it would have been possible to make the game without requiring the use of Xbox Live. [laughs] But back to the comparison between the single- and multiplayer modes, you’ll recall that there were quests in the game. These quests were made for single-player mode, and the exploration pace and frequency of items dropping were the same as in the multiplayer mode. So I think if a player was exploring and trying to collect rare items alone, that would have been quite challenging. If we had made that aspect of the game easier for the single-player mode, there wouldn’t have been any motivation on the part of the player to play the multiplayer mode. It made playing as a group more exciting and rewarding to be able to go into areas that you couldn’t if you were playing alone. You could play the game alone, but it was better when you played with others. That was the conceptual idea.

Speaking of rare items, do you remember which item was the rarest in the game?

The Spread Needle [was pretty rare]. And this wasn’t necessarily the rarest item but ... Agito was also rare. Every class of items had really good, rare items. I can’t remember which was the rarest, but Agito was my favorite. There was a borderline bug/exploit that was discovered by one of the users where if you used one of these wide-ranging weapons that fired shots in all directions, and changed your weapon to a stronger weapon immediately after you fired the first weapon, it would convert the bullets from the first weapon into the bullets of the stronger weapon. The damage on the enemy was calculated by the weapon being held by the character when the damage was made, so by switching over to a stronger weapon before the damage was calculated, the player could exploit the system to create greater damage.

Wow. That’s a handy tip. Is it true that PSO was initially called Third World?

Third World? Did someone say that?

It’s been mentioned elsewhere; it’s possibly an urban legend.

I don’t think so. Before it was called Phantasy Star Online, it wasn’t a sci-fi game. It was a fantasy adventure RPG. In the beginning, the player had their own island and sailed across the sea to other islands to explore. The player would find other characters and materials on the various islands, and bring them back to their own island to make it bigger and stronger. The player would make weapons with the materials brought back to the island, too. The goal was to expand and build your own island and explore with other players. That’s the kind of role-playing game I had in mind at the beginning.

That sounds almost like Skies of Arcadia. Another thing Setsumasa said was that when you first started developing PSO, the camera perspective was isometric, like in Diablo.

He probably had various ideas in the beginning. Everyone submitted ideas, and we had a variety of ideas. Before we had PSO, the question was how were we going to make an online game and we started with that fantasy online game I mentioned. At the time, there was a manga that was very popular called Hunter X Hunter. It was a popular Japanese comic book. We were inspired by that, and made the characters “hunters” and had them exploring their world, discovering interesting items and making comrades through their adventure. There’s a “hunter’s guild” in PSO, and that’s where that concept stems from. But, regarding the isometric view, we weren’t really thinking of doing that.

You worked at Sonic Team for a long time. Did you work on Nights?

I wasn’t involved with Nights, but there’s a spinoff called Christmas Nights. I made that game.

Christmas Nights is great! It features Sonic the Hedgehog and has tons of content. It was a super piece of fan service.

Technically it was free in Japan, as well. It was a pack-in with the Sega Saturn, but for people who already owned a Sega Saturn, we distributed it for free if they sent us the shipping cost. It was designed as a fan service. We made that in two months.

You should be proud of that.

I wasn’t supposed to make it. I was asked to just create the planning document. So I wrote up a two- or three-page planning doc for Christmas Nights and handed it in, saying, “Please go make this.” And I left to go to the U.K. to make Sonic 3D Blast.

You moved to the U.K.?

No, a dev team called Traveller’s Tales in the UK was making the game, and I went for the last two weeks of development. Up until then, I had been working from Japan, sending documents to the UK, reviewing their work, and sending back feedback. But for crunch time, I flew out there to finish the game.

When I returned to Japan two weeks later, nothing had been done with the planning doc I had written for Christmas Nights, and I was told there was nobody else to work on it. So from the day I returned from the U.K., for two months straight, I basically lived at work making Christmas Nights. It was in the peak of summer, and I was holed up at the office listening to “Jingle Bells.” [laughs]

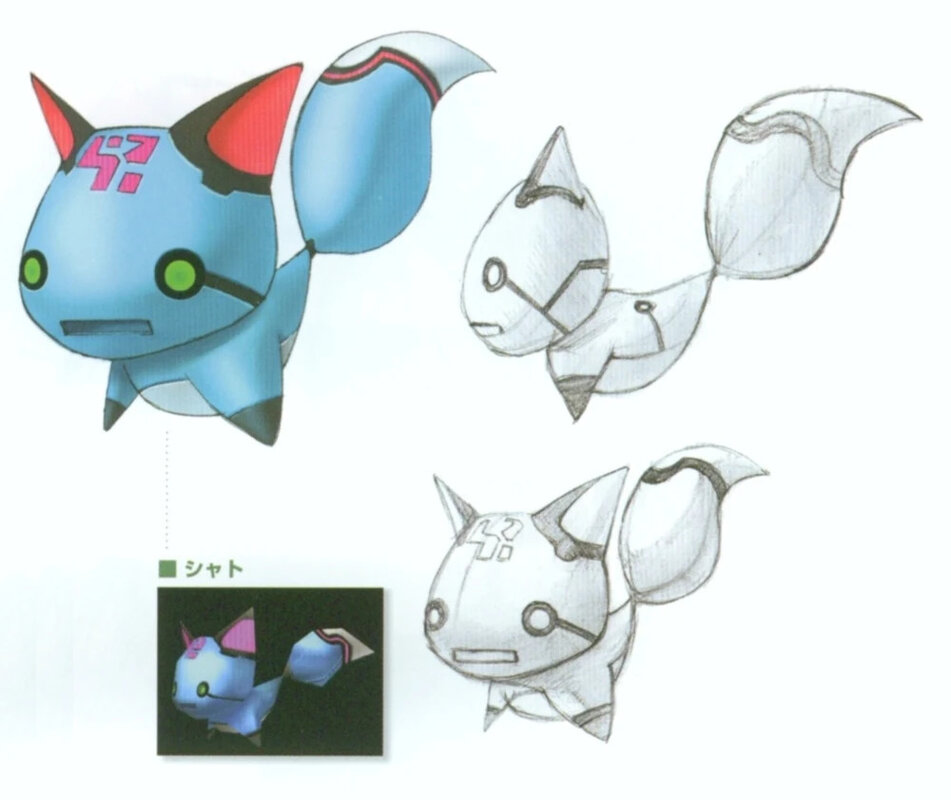

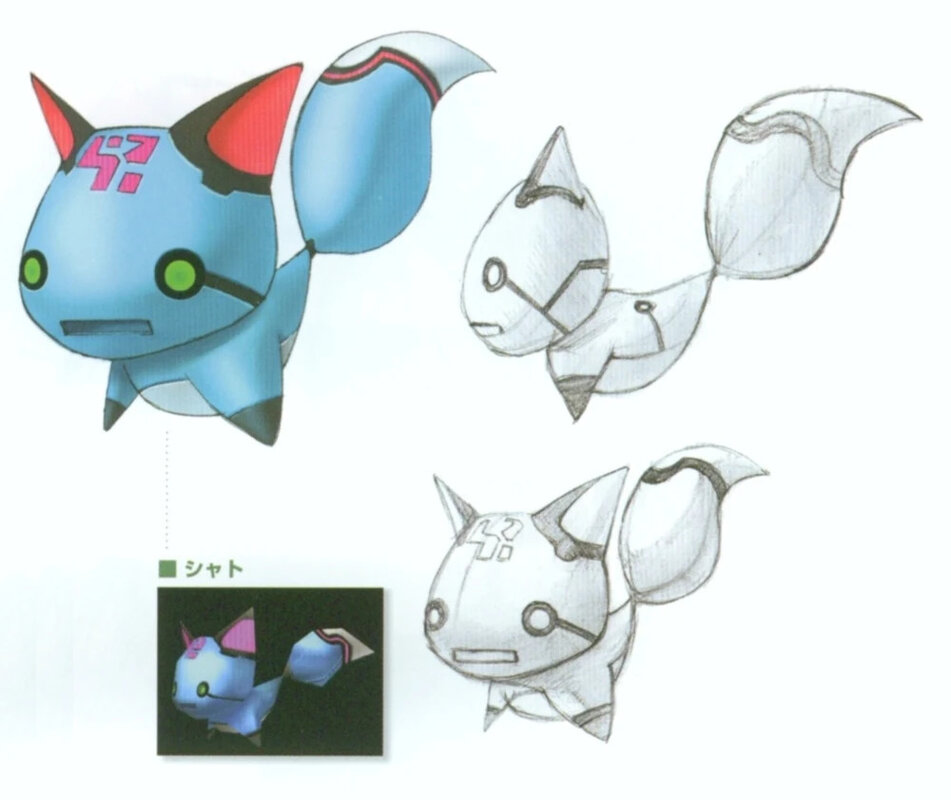

It’s beautifully done, though. The a cappella version of the theme song is gorgeous. The reason for asking about Nights is that it had the Nightopian A-LIFE system. Sonic Adventure had the Chao system, which grew from that, and PSO has the MAGs. It’s really impressive because that “pet” system grew in complexity over time. In PSO it’s almost like a game in a game, because you have to feed the pet, etc. It’s a lot like a Tamagotchi.

It’s beautifully done, though. The a cappella version of the theme song is gorgeous. The reason for asking about Nights is that it had the Nightopian A-LIFE system. Sonic Adventure had the Chao system, which grew from that, and PSO has the MAGs. It’s really impressive because that “pet” system grew in complexity over time. In PSO it’s almost like a game in a game, because you have to feed the pet, etc. It’s a lot like a Tamagotchi.

The A-LIFE system was created in Nights, and that system was used to create the Chao in Sonic Adventure, and that knowhow was passed down to PSO. Initially, the plan was to have players take a dragon’s egg, nurture it, and then raise the dragon that hatched from the egg. Sakai was good at designing dragons so we thought that would be cool, but then we realized the sheer number of dragons that we would have to design for the game, and decided it would be impossible. And if the dragon walked with the player and each player had their own dragon, that would mean there would be eight characters on the screen when playing online. It just became technically impossible; we couldn’t have that many polygons on the screen.

I was told that we could only have a small round character floating in the air above the player’s character. And that’s how we came up with the MAG. We had the idea to incorporate something similar to the A-LIFE system into PSO from the beginning, and we had to come up with a system that would work for the game, and the MAG system is where we landed. We could change the shape of the MAG’s body — we could make it bigger or chubbier — but we couldn’t add clothing. So in order to show some evolutionary elements to the MAG, we adjusted the silhouette and added things to the back like wings, and enlarged it as the MAG got stronger.

So you weren’t part of this system’s evolution from Nights?

So you weren’t part of this system’s evolution from Nights?

No, others at Sonic Team made the A-LIFE system, and it was Naka’s idea to incorporate the A-LIFE system into PSO. I wasn’t involved in Nights in the least. The team that worked on Nights was burned out from working on that title, so that’s why I had to come in and make Christmas Nights.

Do you know who came up with the original idea for the A-LIFE system?

I don’t know for sure. If that person is still at Sega, it might be [Takashi] Iizuka, [the original game designer of Nights].

Were there any concerns in PSO about balance issues?

One of the ideas from the early concept stage was to let players enjoy playing the game as different characters. So there was a variety of weapons and MAG types to help a player become a stronger character. We didn’t want to hinder the player’s curiosity of trying different characters or experiencing different play styles within the game by forcing them to invest so much time and effort into one character. One way we thought we could encourage players to play different characters was if they could transfer their MAG.

We also removed the first part, of having to nurture your MAG from birth, and instead let players jump straight into being able to play the game with a completely leveled-up MAG. One of the downsides of online games is that it’s difficult for people of different levels to play together. Again, from the concept stage, we wanted to try to eliminate any barriers that would prevent people from playing together, regardless of your level or ability. I think we were successful in creating this balanced MAG system that allowed us to achieve these things.

Being able to take a fully developed MAG and giving it to a completely new character to not be totally weak, even with a level 1 character at the start of the game, was a great idea. Were there ever any more of the established character classes that were dropped because of time or development reasons?

Not any of the playable character classes, but there were NPCs that were cut. When we decided to use the Phantasy Star lore, there was an enemy character called Rutsu. We were initially planning on including this character. I had envisioned a scenario where there’s a fossil in the lowest level of the game. That fossil is a spaceship with Dark Falz, an enemy character from Phantasy Star, sealed inside. The force that is keeping Dark Falz inside the spaceship is a witch called Rutsu, but her concentration and strength is weakening, and Dark Falz is beginning to break free from her grip. We had discussed all of this, but it was cut from the finished game.

The reason?

We couldn’t get around to implementing the cutscenes and incorporating any more new characters into the game.

The Dreamcast version allowed for the capture of screenshots of the game. This is something that we take for granted now in gaming hardware, but this was yet another pioneering thing that PSO did before anybody else on a console. Why did you attempt it? This was before social media really existed.

There was no social media, but the internet was beginning to filter through to the masses, and people were starting to create their personal homepages. We wanted people to write and talk about PSO on their homepages, right? And we thought it would be more effective if they could take their own screenshots to upload to their website. We figured it would be a useful tool that players would use to talk about PSO on their personal sites. When players took a screenshot, it would be saved onto Sega’s Visual BBS website, and could then be downloaded onto the player’s PC to be used on their website. At the time, it was quite a hassle to try to save console screenshots and save them onto your PC, so we included a tool that would simplify that process for the player.

Other online multiplayer console games like Final Fantasy 11 removed player names from in-game screenshots for privacy reasons. Did you have to do similar things for privacy issues, or was that not a concern yet?

The Visual BBS saved exactly what was on the player’s screen.

Does that feature still work today?

You would have to be connected online, and I’m not sure if it’s accessible overseas. Japanese users were uploading it to the Visual BBS site, so I don’t know if the overseas version retained this feature.

People who read about this might wonder about it now. Did the GameCube version also have this feature?

I think it did. It was a port, so it should have included the same features. The files were quite big, and the GameCube had such a small amount of memory to begin with; the memory card would only have enough room for one save file and one screenshot. So it’s possible that it doesn’t exist on the GameCube version.

That makes sense. When working on Phantasy Star Universe as the producer, what did you want to retain from PSO, and what did you want to change for PSU?

That makes sense. When working on Phantasy Star Universe as the producer, what did you want to retain from PSO, and what did you want to change for PSU?

There were a few things that we couldn’t accomplish in PSO. I mentioned earlier that an early concept was to have the players start on islands and to travel to other islands to discover and explore. Another thing was to have your own room and make your own shop, display items for sale, etc. These were ideas that were dropped early in the planning stages of PSO, but we were able to include [them] in PSU. Also, for PSU we were able to store save data on the online server. And for PSO, we were only able to focus on the gameplay elements of the game, so for PSU, I wanted to focus more on the story elements of the game. Those three points are things that we didn’t do in PSO that we were able to do in PSU.

In hindsight, do you have any idea why PSU wasn’t as universally adored as PSO?

Actually, in terms of number of sales, PSU sold better. Maybe not overseas, but at least in Japan, PSU sold better. We also released a PSP version of PSU, which increased the user base, so I think that was positive. One thing I can think of is that maybe the online multiplayer element wasn’t as appealing. The visual effects of the battles and magic spells became more elaborate, and there was less focus on the strategy aspects for the player. Since there were fewer options for the player in PSO, players had to get creative in their strategies.

Did you work on Phantasy Star Online Episode 3: CARD Revolution?

I didn’t have much to do with it.

Especially after how good the first PSO was, and how high the expectations were for the next game, nobody expected a card battle game, because it’s a very different kind of game. Was there as much disappointment in Japan as there was in the U.S.?

I wasn’t involved with that title, but there were members on the PSO team that wanted to make a card battle game and they wanted to add a PSO spin to it, so they went off and made that game. But I wasn’t involved, so it’s hard for me to comment on that.

It was disappointing because it had the PSO name attached to it. If they had called it something like Rappy’s Card Battle, nobody would have been upset. Probably.

If it was a game I had made, I could respond to the criticism, but there are politics involved when commenting on other people’s work. But I can see how fans of PSO would be disappointed if they were hyped to hear another game was coming out, and then to find out that the new PSO game was a card game.

Smartphones and portable devices are so much stronger than consoles from back then that it seems like Sega could easily put the original PSO on a new device. It’s such a great game and so many people still want to play the original game ... people still run private Blue Burst servers. Would you like to see PSO released on something modern?

Sure, I think it would be nice to see PSO on a modern device. It’s Sega’s property, so it’s not something I can comment on with any kind of authority. But I think PSO was a good game, so I don’t see why not.

In your opinion, what’s the best version of PSO to play? Blue Burst?

Yeah, Blue Burst.

It’s impossible to find now.

Well, you can’t play that version anyway, because the servers are down. If you want to play the normal version, probably the GameCube version, then. There are probably fan-made servers, so the Dreamcast version might still be playable.

Blue Burst can’t be played offline, right?

No. You can only play online. If Sega will hire me, I’ll make another version. [laughs]

Here’s another thing. It seems like PSO would be the easiest merchandising opportunity. MAG merch, blind boxes, you name it.

How about a Kickstarter campaign? We could probably do it with about 100 million yen [approximately $1 million].

Sega PR: How about running the online side?

We’ll keep it to a minimum. Just keep the servers running. [laughs]

Is there anything you would like to say to the fans?

I feel very grateful to be interviewed for a game that was released 20 years ago. I don’t think I would have been interviewed if it was a boring game, so I’m glad I was able to create a game that has left a lasting impression on the players. I feel proud, and I’ll try to feel proud about releasing Christmas Nights, too.

The web page from which the original interview is taken can be found here

Let’s start by having you explain your role on the team. You were the director of PSO, but that can mean a lot of different things depending on the situation.

Let’s start by having you explain your role on the team. You were the director of PSO, but that can mean a lot of different things depending on the situation.Takao Miyoshi: I did the planning and original concept for the game. [...] I was more of a director and supervised the overall project. At first the planning document was just a single piece of paper, then it expanded from there. If we go back to the very beginning of it all, it goes back to the Sega Saturn. We were trying to make an online game on the Saturn for a long time. That’s when we first started exploring online gaming. At the time, I was working on a game called Burning Rangers. It was initially created as a network-compatible game with four players who go on a rescue mission. But there were network issues that we couldn’t overcome, so it was released as a regular, offline game. That was a game that I had created with online in mind but [in which the online part] didn’t make it past the planning stage.

Wow, Burning Rangers was originally planned as a four-player online game?

There’s a lot of flying around in that game and the maps are very complicated. So for PSO we said, “No flying allowed!” because that made things too complicated. That’s why you can’t leave the ground in PSO.

This changed for PSO2, obviously.

This changed for PSO2, obviously.Yeah, you can jump and fly in PSO2. [But for PSO] we found that it became difficult to navigate your character when they were flying in a 3D space, so we decided it was best to keep the player on the ground.

It’s interesting that you mention jumping because when I spoke with the programming team, we discussed whether jumping was removed to avoid having to transmit too much data back and forth. It seemed like it was for practical reasons but now you’re saying that it was also for spatial reasons.

Yes, [program director Akio] Setsumasa handled all the server-related programming. He’s the one who said definitely no jumping in PSO. I concurred and that’s how we made the game. We had to decide what kind of navigation would be network-friendly. You might notice in PSO, it’s a lot like Diablo, where there are a lot of points that you can warp to. The reason why those points are so deliberately set is because if you’re playing online, there would be enough time between points where data could sync up and everyone playing would be in the same location. There wouldn’t be any lag where one player gets ahead of another player.

We’re approaching two decades since the game’s release, and you were 20 years younger when it came out. Looking back, what is your impression of PSO now?

I was about 30 years old when I created PSO and I quit Sega when I turned 40. I worked on the series — PSO, Phantasy Star Universe, and Phantasy Star Online 2 — almost up until the release of PSO2. So PSO was my life for about a decade. And now it’s been about another decade since leaving the series. Since that time, I’ve been studying and working on different things.

The thing that stands out is that I was so young. If I had known the complexities of creating and running an online game such as PSO, I probably would never have made it the way it turned out. I would have made prudent decisions and figured out how to simplify it. We didn’t really understand what it was going to take, so we took many risks and pushed things through. Consequently, that was probably the right move. The “Word Select System” is a good example. I don’t ever want to make something like that again.

Perhaps the word “recklessness” isn’t the right word, but that sort of risk-taking, where you’re less cautious because you’re young, is probably what allowed you to achieve a lot of what you did.

I’ve become wiser, right. I know that if I do this then that will happen. Which means I’m looking for efficiency and the path of least resistance. I think that leads to making familiar games where the path is clear and the return can be maximized. But at the time, everything was new and we couldn’t foresee anything, so every step we took was uncharted territory. There’s a certain amount of risk in that kind of environment and as you get older, you become risk-averse. When you’re young, you’re not thinking with your head, so you can charge into areas without even recognizing it as a risk. I think there was an element of youthful enthusiasm that pushed the game through.

One person that was not young at the time and supported the team was Isao Okawa, former chairman of CSK and Sega. He even pumped $800 million of his own money into the company at one point to make sure the development teams could continue to make games that only Sega could make. So here was an older executive at the top of the company taking risks, too.

PSO wouldn’t have existed without him. At the time, the No. 1 thing for Sega was how to blow people away by making something new. That was probably the biggest factor.

Yeah, it was a great period. PSO was a pioneering game and this was your first game as a director. How did you navigate through that pressure?

The pressure was intense. This probably won’t make it into the article but this was around the time when North Korea launched a missile over Japan and it landed in the Pacific. I remember thinking that if the missile had landed in Tokyo, it would delay the launch. It would cause such a commotion that we would have to delay the launch, and we would have more time to work on the game. [laughs] That’s how psychotic I was at the time.

Did PSO launch pretty much on time or did it suffer a lot of setbacks?

It didn’t launch as originally planned, but ... it came out in 2000, right? We wanted to release it before the 21st century, so 2001, and I think it came out at the very end of 2000. So, we just made the drop-dead deadline. But it was a forced release. There were still quite a few bugs left in the game.

Obviously, you had gained the confidence of Naka by that time. Why do you think he entrusted you to be the director of PSO?

Obviously, you had gained the confidence of Naka by that time. Why do you think he entrusted you to be the director of PSO?Put bluntly, while I was the main planner for Burning Rangers, I also did the scheduling and solidifying of the game’s concept design, so I was practically doing the work of a managing director under the title of “main planner.” So, when it came time for PSO, I think they decided to give me the title. [Satoshi] Sakai was in charge of the art design, [Akio] Setsumasa and [Yasuhiro] Takahashi were in charge of the programming, and I was put in charge of the overall project, including planning. Naka was the producer, and basically came up with the overall vision of creating a global sci-fi RPG and handled the business-to-business situations, while I was the one who did all the promotional outreach and behind-the-scenes directorial types of things.

What sort of guidance and input did Naka provide during the development of the game?

Naka was very involved and provided a lot of ideas that were challenging to implement. He would tell me, “We should do this,” or, “We should do that.” Some of his ideas were seemingly impossible, but we would struggle and make them happen, and that’s how PSO became the final game. So I think that it’s thanks to Naka’s impossible orders that we were able to create something unique.

Because Naka began his career as a programmer, do you think that background helped him in coming up with ideas for the game from a producer’s standpoint?

Naka’s concern was not for how hard the work was going to be for the team. His concern was that the ideas were awesome and had to be included in the game so that the game would be great. His philosophy was “you don’t know until you try it,” and ideas didn’t stem from whether it was possible or “hey, this would help make our job easier.” They came from pure enthusiasm: “We’re going to do this, so you’ve gotta go make this happen.” So we’d take those ideas or problems, put our heads together, and figure out solutions. We were creating things that didn’t exist, so we would come up with possible solutions and try to convince him that what we came up with was practical and worked better than his initial ideas.

The process doesn’t sound super fun.

It wasn’t really fun, but it’s the way a genius works. He would never bend on his ideas. Once he had an idea, it was impossible to steer him away.

He was unwavering?

Some people would say that. He was very strict. But, that’s why we were able to accomplish something that wasn’t possible under normal circumstances. I think consequently that’s what made the game fun.

How did Sakai’s prior experience and talent affect the outcome of the game?

How did Sakai’s prior experience and talent affect the outcome of the game?He was the [visual] designer for the game and established the game’s environment. You’ve interviewed him in the past, so I’m sure you’re aware, but he was the designer of Azel and many of the dragons in Panzer Dragoon Saga. I think PSO benefited from his prior experience, just like with all of us. My prior experience on Burning Rangers and Sonic games, Panzer Dragoon for him, and Setsumasa brought his knowledge of network gaming. It was a combined effort of everyone’s unique experiences.

Was Sakai responsible for the character designs and other areas?

He was in charge of the game’s overall visual design, including character design and style. His specialty is designing monsters and dragons. The dragon in the first big battle of PSO is quite symbolic. That was all Sakai’s work.

For Panzer Dragoon, he not only did the design for the dragons but also for the dragon ‘morphing’ system. He is an animator and a modeler who could do many things. Was he able to have a similar kind of impact on PSO? Players can change the size and shape of their created characters, for instance — was that idea part of his contribution?

For Panzer Dragoon, he not only did the design for the dragons but also for the dragon ‘morphing’ system. He is an animator and a modeler who could do many things. Was he able to have a similar kind of impact on PSO? Players can change the size and shape of their created characters, for instance — was that idea part of his contribution?Yes, we utilized his experience from his work on Panzer Dragoon Saga with morphing the dragon, and decided to incorporate that into PSO, primarily because Sakai had the knowhow to do that.

Obviously, Diablo was a big influence on PSO. How much of Diablo did you play yourself?

I played quite a lot. Nobody on our team had worked on an online game, so one of the challenges was getting the team to understand what made online games fun. I had a lot of people play the game, but a lot of them were turned off by the dark fantasy. They would say, “it’s disturbing,” or, “I don’t get why it’s fun.” Trying to unify the team and getting them to understand the direction we wanted to take the game in was very difficult.

Did you have LAN parties, where you played in a controlled environment so that the team could understand the cooperative elements?

Did you have LAN parties, where you played in a controlled environment so that the team could understand the cooperative elements?We installed Diablo on everyone’s PC in the office and had a closed LAN and spent many days playing together so that the team could learn what network gaming was all about.

Was there a point where you saw people starting to get the appeal, like the satisfaction of seeing a rare item drop, where you felt the team really get into the game?

Some people like Setsumasa stayed around until 10 or 11 p.m. at night after people left the office. He would connect Diablo to the network and play until morning, wake up to work, and then play again. Some of us weren’t going home much at the time. Some people would go home just to bathe, sleep a few hours, come back into the office to work, and then play Diablo at the office. It was mostly in the name of research, though. There are a number of games that we used as inspiration. Diablo was obviously one of them. I had heard that Dragon Quest was inspired by remaking Ultima with a Japanese audience in mind. So our concept was, “Let’s make a Diablo game that would appeal to the Japanese audience.”

With good results. Even though Diablo is a distinctly American game, PSO feels like a very distinctly Japanese game. And yet, it’s not just palatable to Japanese gamers but to everyone.

I think Diablo is an amazing game, but it’s not a game that appeals to Japanese players. Our suspicion was that Japanese gamers would prefer to cooperate and work together to defeat something more than to compete and fight against other players. That’s why we created PSO to be a cooperative role-playing game. Diablo has cooperative elements but it also has PK and an element of killing other player characters. We eliminated those elements and focused on how we could make a fun, cooperative RPG experience. I think that’s the biggest difference between PSO and Diablo.

The single-player in PSO is almost exactly the same as the multiplayer, though when you’re playing alone, it can be tedious because you have to zone out and return to attack before you get surrounded by enemies. When you’re playing multiplayer, that’s when something magical happens, because the cooperative elements make it so much more fair and fun.

We did adjust the difficulty level between characters for single-player and multiplayer, so single-player mode should have been a little easier to play, I think. The number of monsters that appeared was a little smaller, etc. It was our first online game, so we had to make sure that it could be played as a single-player game. But at the same time, we did spend a lot of time developing for the multiplayer experience, so single-player might have come off feeling a little more challenging.

Speaking of the online multiplayer experience, when the Xbox version came out, it was the first version where it was mandatory to be online. This was at a time when being online all the time was still difficult, due to internet speeds, lack of broadband, etc. You had to have Xbox Live even to play the single-player mode. A lot of people didn’t like that because you couldn’t play the single-player mode offline.

I forgot about that. I think it was Microsoft’s request. It was at a time when they wanted to make Xbox Live attractive, so I think they wanted a title that required Xbox Live. Of course, it would have been possible to make the game without requiring the use of Xbox Live. [laughs] But back to the comparison between the single- and multiplayer modes, you’ll recall that there were quests in the game. These quests were made for single-player mode, and the exploration pace and frequency of items dropping were the same as in the multiplayer mode. So I think if a player was exploring and trying to collect rare items alone, that would have been quite challenging. If we had made that aspect of the game easier for the single-player mode, there wouldn’t have been any motivation on the part of the player to play the multiplayer mode. It made playing as a group more exciting and rewarding to be able to go into areas that you couldn’t if you were playing alone. You could play the game alone, but it was better when you played with others. That was the conceptual idea.

Speaking of rare items, do you remember which item was the rarest in the game?

The Spread Needle [was pretty rare]. And this wasn’t necessarily the rarest item but ... Agito was also rare. Every class of items had really good, rare items. I can’t remember which was the rarest, but Agito was my favorite. There was a borderline bug/exploit that was discovered by one of the users where if you used one of these wide-ranging weapons that fired shots in all directions, and changed your weapon to a stronger weapon immediately after you fired the first weapon, it would convert the bullets from the first weapon into the bullets of the stronger weapon. The damage on the enemy was calculated by the weapon being held by the character when the damage was made, so by switching over to a stronger weapon before the damage was calculated, the player could exploit the system to create greater damage.

Wow. That’s a handy tip. Is it true that PSO was initially called Third World?

Third World? Did someone say that?

It’s been mentioned elsewhere; it’s possibly an urban legend.

I don’t think so. Before it was called Phantasy Star Online, it wasn’t a sci-fi game. It was a fantasy adventure RPG. In the beginning, the player had their own island and sailed across the sea to other islands to explore. The player would find other characters and materials on the various islands, and bring them back to their own island to make it bigger and stronger. The player would make weapons with the materials brought back to the island, too. The goal was to expand and build your own island and explore with other players. That’s the kind of role-playing game I had in mind at the beginning.

That sounds almost like Skies of Arcadia. Another thing Setsumasa said was that when you first started developing PSO, the camera perspective was isometric, like in Diablo.

He probably had various ideas in the beginning. Everyone submitted ideas, and we had a variety of ideas. Before we had PSO, the question was how were we going to make an online game and we started with that fantasy online game I mentioned. At the time, there was a manga that was very popular called Hunter X Hunter. It was a popular Japanese comic book. We were inspired by that, and made the characters “hunters” and had them exploring their world, discovering interesting items and making comrades through their adventure. There’s a “hunter’s guild” in PSO, and that’s where that concept stems from. But, regarding the isometric view, we weren’t really thinking of doing that.

You worked at Sonic Team for a long time. Did you work on Nights?

I wasn’t involved with Nights, but there’s a spinoff called Christmas Nights. I made that game.

Christmas Nights is great! It features Sonic the Hedgehog and has tons of content. It was a super piece of fan service.

Technically it was free in Japan, as well. It was a pack-in with the Sega Saturn, but for people who already owned a Sega Saturn, we distributed it for free if they sent us the shipping cost. It was designed as a fan service. We made that in two months.

You should be proud of that.

I wasn’t supposed to make it. I was asked to just create the planning document. So I wrote up a two- or three-page planning doc for Christmas Nights and handed it in, saying, “Please go make this.” And I left to go to the U.K. to make Sonic 3D Blast.

You moved to the U.K.?

No, a dev team called Traveller’s Tales in the UK was making the game, and I went for the last two weeks of development. Up until then, I had been working from Japan, sending documents to the UK, reviewing their work, and sending back feedback. But for crunch time, I flew out there to finish the game.

When I returned to Japan two weeks later, nothing had been done with the planning doc I had written for Christmas Nights, and I was told there was nobody else to work on it. So from the day I returned from the U.K., for two months straight, I basically lived at work making Christmas Nights. It was in the peak of summer, and I was holed up at the office listening to “Jingle Bells.” [laughs]

It’s beautifully done, though. The a cappella version of the theme song is gorgeous. The reason for asking about Nights is that it had the Nightopian A-LIFE system. Sonic Adventure had the Chao system, which grew from that, and PSO has the MAGs. It’s really impressive because that “pet” system grew in complexity over time. In PSO it’s almost like a game in a game, because you have to feed the pet, etc. It’s a lot like a Tamagotchi.

It’s beautifully done, though. The a cappella version of the theme song is gorgeous. The reason for asking about Nights is that it had the Nightopian A-LIFE system. Sonic Adventure had the Chao system, which grew from that, and PSO has the MAGs. It’s really impressive because that “pet” system grew in complexity over time. In PSO it’s almost like a game in a game, because you have to feed the pet, etc. It’s a lot like a Tamagotchi.The A-LIFE system was created in Nights, and that system was used to create the Chao in Sonic Adventure, and that knowhow was passed down to PSO. Initially, the plan was to have players take a dragon’s egg, nurture it, and then raise the dragon that hatched from the egg. Sakai was good at designing dragons so we thought that would be cool, but then we realized the sheer number of dragons that we would have to design for the game, and decided it would be impossible. And if the dragon walked with the player and each player had their own dragon, that would mean there would be eight characters on the screen when playing online. It just became technically impossible; we couldn’t have that many polygons on the screen.

I was told that we could only have a small round character floating in the air above the player’s character. And that’s how we came up with the MAG. We had the idea to incorporate something similar to the A-LIFE system into PSO from the beginning, and we had to come up with a system that would work for the game, and the MAG system is where we landed. We could change the shape of the MAG’s body — we could make it bigger or chubbier — but we couldn’t add clothing. So in order to show some evolutionary elements to the MAG, we adjusted the silhouette and added things to the back like wings, and enlarged it as the MAG got stronger.

So you weren’t part of this system’s evolution from Nights?

So you weren’t part of this system’s evolution from Nights?No, others at Sonic Team made the A-LIFE system, and it was Naka’s idea to incorporate the A-LIFE system into PSO. I wasn’t involved in Nights in the least. The team that worked on Nights was burned out from working on that title, so that’s why I had to come in and make Christmas Nights.

Do you know who came up with the original idea for the A-LIFE system?

I don’t know for sure. If that person is still at Sega, it might be [Takashi] Iizuka, [the original game designer of Nights].

Were there any concerns in PSO about balance issues?

One of the ideas from the early concept stage was to let players enjoy playing the game as different characters. So there was a variety of weapons and MAG types to help a player become a stronger character. We didn’t want to hinder the player’s curiosity of trying different characters or experiencing different play styles within the game by forcing them to invest so much time and effort into one character. One way we thought we could encourage players to play different characters was if they could transfer their MAG.

We also removed the first part, of having to nurture your MAG from birth, and instead let players jump straight into being able to play the game with a completely leveled-up MAG. One of the downsides of online games is that it’s difficult for people of different levels to play together. Again, from the concept stage, we wanted to try to eliminate any barriers that would prevent people from playing together, regardless of your level or ability. I think we were successful in creating this balanced MAG system that allowed us to achieve these things.

Being able to take a fully developed MAG and giving it to a completely new character to not be totally weak, even with a level 1 character at the start of the game, was a great idea. Were there ever any more of the established character classes that were dropped because of time or development reasons?

Not any of the playable character classes, but there were NPCs that were cut. When we decided to use the Phantasy Star lore, there was an enemy character called Rutsu. We were initially planning on including this character. I had envisioned a scenario where there’s a fossil in the lowest level of the game. That fossil is a spaceship with Dark Falz, an enemy character from Phantasy Star, sealed inside. The force that is keeping Dark Falz inside the spaceship is a witch called Rutsu, but her concentration and strength is weakening, and Dark Falz is beginning to break free from her grip. We had discussed all of this, but it was cut from the finished game.

The reason?

We couldn’t get around to implementing the cutscenes and incorporating any more new characters into the game.

The Dreamcast version allowed for the capture of screenshots of the game. This is something that we take for granted now in gaming hardware, but this was yet another pioneering thing that PSO did before anybody else on a console. Why did you attempt it? This was before social media really existed.

There was no social media, but the internet was beginning to filter through to the masses, and people were starting to create their personal homepages. We wanted people to write and talk about PSO on their homepages, right? And we thought it would be more effective if they could take their own screenshots to upload to their website. We figured it would be a useful tool that players would use to talk about PSO on their personal sites. When players took a screenshot, it would be saved onto Sega’s Visual BBS website, and could then be downloaded onto the player’s PC to be used on their website. At the time, it was quite a hassle to try to save console screenshots and save them onto your PC, so we included a tool that would simplify that process for the player.

Other online multiplayer console games like Final Fantasy 11 removed player names from in-game screenshots for privacy reasons. Did you have to do similar things for privacy issues, or was that not a concern yet?

The Visual BBS saved exactly what was on the player’s screen.

Does that feature still work today?

You would have to be connected online, and I’m not sure if it’s accessible overseas. Japanese users were uploading it to the Visual BBS site, so I don’t know if the overseas version retained this feature.

People who read about this might wonder about it now. Did the GameCube version also have this feature?

I think it did. It was a port, so it should have included the same features. The files were quite big, and the GameCube had such a small amount of memory to begin with; the memory card would only have enough room for one save file and one screenshot. So it’s possible that it doesn’t exist on the GameCube version.

That makes sense. When working on Phantasy Star Universe as the producer, what did you want to retain from PSO, and what did you want to change for PSU?

That makes sense. When working on Phantasy Star Universe as the producer, what did you want to retain from PSO, and what did you want to change for PSU?There were a few things that we couldn’t accomplish in PSO. I mentioned earlier that an early concept was to have the players start on islands and to travel to other islands to discover and explore. Another thing was to have your own room and make your own shop, display items for sale, etc. These were ideas that were dropped early in the planning stages of PSO, but we were able to include [them] in PSU. Also, for PSU we were able to store save data on the online server. And for PSO, we were only able to focus on the gameplay elements of the game, so for PSU, I wanted to focus more on the story elements of the game. Those three points are things that we didn’t do in PSO that we were able to do in PSU.

In hindsight, do you have any idea why PSU wasn’t as universally adored as PSO?

Actually, in terms of number of sales, PSU sold better. Maybe not overseas, but at least in Japan, PSU sold better. We also released a PSP version of PSU, which increased the user base, so I think that was positive. One thing I can think of is that maybe the online multiplayer element wasn’t as appealing. The visual effects of the battles and magic spells became more elaborate, and there was less focus on the strategy aspects for the player. Since there were fewer options for the player in PSO, players had to get creative in their strategies.

Did you work on Phantasy Star Online Episode 3: CARD Revolution?

I didn’t have much to do with it.

Especially after how good the first PSO was, and how high the expectations were for the next game, nobody expected a card battle game, because it’s a very different kind of game. Was there as much disappointment in Japan as there was in the U.S.?

I wasn’t involved with that title, but there were members on the PSO team that wanted to make a card battle game and they wanted to add a PSO spin to it, so they went off and made that game. But I wasn’t involved, so it’s hard for me to comment on that.

It was disappointing because it had the PSO name attached to it. If they had called it something like Rappy’s Card Battle, nobody would have been upset. Probably.

If it was a game I had made, I could respond to the criticism, but there are politics involved when commenting on other people’s work. But I can see how fans of PSO would be disappointed if they were hyped to hear another game was coming out, and then to find out that the new PSO game was a card game.

Smartphones and portable devices are so much stronger than consoles from back then that it seems like Sega could easily put the original PSO on a new device. It’s such a great game and so many people still want to play the original game ... people still run private Blue Burst servers. Would you like to see PSO released on something modern?

Sure, I think it would be nice to see PSO on a modern device. It’s Sega’s property, so it’s not something I can comment on with any kind of authority. But I think PSO was a good game, so I don’t see why not.

In your opinion, what’s the best version of PSO to play? Blue Burst?

Yeah, Blue Burst.

It’s impossible to find now.

Well, you can’t play that version anyway, because the servers are down. If you want to play the normal version, probably the GameCube version, then. There are probably fan-made servers, so the Dreamcast version might still be playable.

Blue Burst can’t be played offline, right?

No. You can only play online. If Sega will hire me, I’ll make another version. [laughs]

Here’s another thing. It seems like PSO would be the easiest merchandising opportunity. MAG merch, blind boxes, you name it.

How about a Kickstarter campaign? We could probably do it with about 100 million yen [approximately $1 million].

Sega PR: How about running the online side?

We’ll keep it to a minimum. Just keep the servers running. [laughs]

Is there anything you would like to say to the fans?

I feel very grateful to be interviewed for a game that was released 20 years ago. I don’t think I would have been interviewed if it was a boring game, so I’m glad I was able to create a game that has left a lasting impression on the players. I feel proud, and I’ll try to feel proud about releasing Christmas Nights, too.